Maltby Miners Memorial Community Group

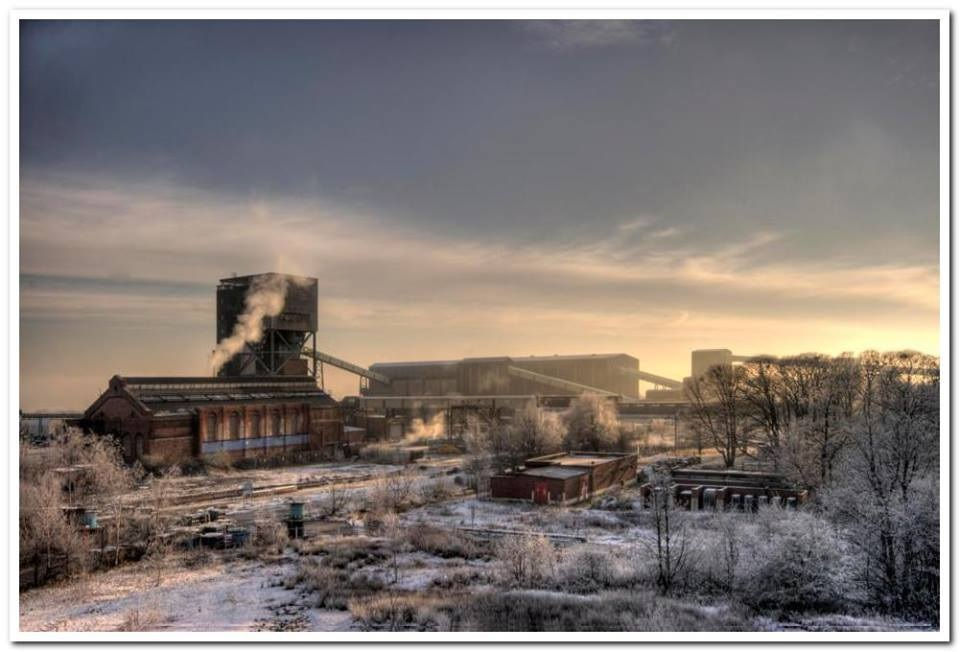

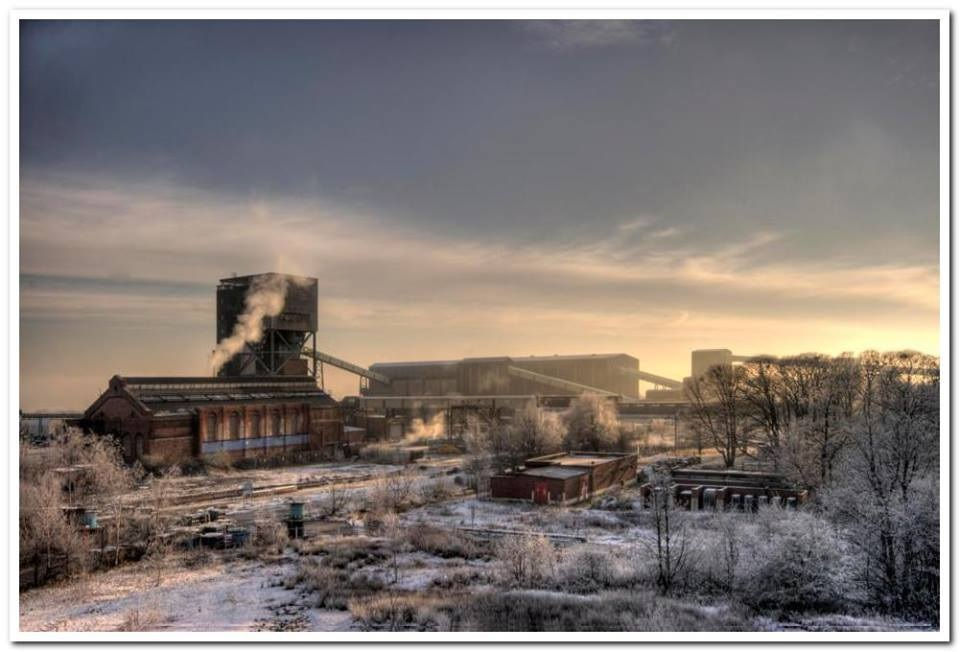

Maltby pit

maltby miners memorial community group

Maltby pit

MALTBY COLLIERY

A short history of Maltby Colliery written by

William J. Spilsbury

Making the Pit Possible

Two factors combined to make sinking a pit in Maltby a terrific challenge. The first was the geology of the 'concealed coalfield 'around Doncaster, which meant that the coal in the Maltby area was very deep, making it costly to reach and difficult to exploit. The second factor was the absence of a convenient railway. However, in spite of the difficulties, it was decided that, when the time was ripe, Maltby Colliery would be sunk on a site in Maltby Wood (at that time in the Parish of Stainton) on the 10th Earl of Scarbrough’s Sandbeck Estate.

Railway Proposals and the principal Minerals Lease.

In 1903 a total of five railway companies got together to seek Parliamentary powers to extend a line northwards, as the South Yorkshire Joint Line, from the projected Shireoaks to Dinnington Branch. Its route was to be via Brookhouse, Slade Hooton, Maltby Wood, Stainton, Tickhill and Potteric Carr Junction (later called St Catherine's) at Doncaster, to join the Great Central line at Kirk Sandall. On 21st March 1904, a minerals lease was sealed between the 10th Earl of Scarbrough and the Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Company Ltd which was then active at Dinnington. The railway route was started in 1905 and required much civil engineering and consequently progress was slow.

Sinking the Pit

The Maltby Main Colliery Company was registered in 1906 and a small site to accommodate the colliery shafts was 'pegged out' in that year. The first jobs carried out were tree felling and the piping of water from a local spring to enable a borehole to be made on the site of number 1 shaft in order to assess the geology. The first sod was cut at that time in the presence of Lord and Lady Scarbrough. Later in March 1907, and with the SYJ railway still under construction, the Colliery Company took the decision to put in temporary sidings and a link to the light railway used to support the railway contractors building operations. This enabled materials to be brought into the colliery to prepare for the sinking. Late August 1907 saw site clearance to accommodate the first six huts for the workmen to live in. The sinking of number 1 shaft is thought to have commenced on the 28th August followed closely by the start of number 2 shaft.

The Sinkers

The sinkers were an unruly assortment of men and many letters of complaint were sent to Lord Scarbrough. In October 1907, Mr Nicholson who was the tenant of Stainton Manor Farm wrote the following to Lord Scarbrough’s agent.

'I must draw your attention to the fact that all the men working at the colliery and who live in Stainton, and that direction, are crossing my land. There is no road to the workings and at least twenty men trespass daily on my land.'

Although Mr Nicholson’s problems were to continue, the building of additional huts in the pit yard, by early 1908, meant that some of the men who had found digs in the nearby villages were now spared the long walk to work.

The sinkers used 'hoppits' to wind out excavated material. These were, in essence, large metal buckets hauled up and down by chains. They were also used to remove water from the shafts before it became feasible to install pumps. The men protected themselves by wearing oilskins and sou'westers and were described as 'looking like lifeboat men'. Sinking was strenuous, demanding and extremely dangerous and there were a number of fatalities. The first three were: Arthur Horton, Sam Saunders and Charles Simons who were all sinkers and died as a result of an accident on the 31st March 1909. George Henry Goodgrove, another sinker, was the fourth man to lose his life when he fell into the shaft on the 19th August 1909. Water was a particular problem in number 1 shaft and pump lodges had to be built into the shaft sides.

Colliery Tin Town

Surface plans of early 1908 show three long rows of huts running parallel to each other in lines north west of the shafts. These were built largely of wood with roofs of corrugated iron. The plan shows different designs suggesting a variety of functions perhaps embracing offices, workshops, bunkhouses and dwellings of more than one type. Due to demand the houses were all in multiple occupation. An extract from a letter written by Annie Sykes (daughter of the head sinker) gives a feel of the conditions that existed in Tin Town.

'I think we were the first to live in the wood. Trees were chopped down so we could find our way out. It was a mass of primroses and violets. In some of the huts there were more drinks sold than were sold in the hotels and pubs in the nearby villages. If there was any fighting they sent for my dad'.

The pit site was a long way from shops and John Thorpe of Conisborough was a travelling trader who used a horse and cart to transport medicines and dry goods for sale to the sinkers and their families. Local food sources were also very tempting and letters from Mr Nicholson talk of trespassing, poaching and thefts of potatoes, turnip tops and fowls. In order to to curb poaching, Lord Scarbrough's agent sought restrictions on sinkers keeping dogs in Tin Town. He also asked that people keeping poultry in Tin Town should pen them in rather than let them scratch about in the wood. It was apparent that alcohol was an issue by a letter from Mr Nicholson in 1909.

'I must say that since the last accident at the pit men have been continually drinking and the place is a perfect 'HELL'. My potatoes and turnips are going every day. I am always complaining but the company takes no notice. If you summons them they get worse and threaten to burn your place down'.

Mr Nicholson's letters also talk of children being sent on trivial errands to Stainton. In 1909 a school was set up in the pit yard to meet the needs of at least, some of the children. This school was known as the Tin Town School. The schoolmaster was a Mr Spencer and the school remained until the opening of the Crags School in 1912.

Finding Coal

On the 18th June 1910 the Managing Director of the Colliery Company sent the following telegram to Lord Scarbrough:

'Barnsley coal proved at Maltby. Five feet two inches workable coal at a depth of 898 yards.

The find was made in number 2 shaft. The total thickness of the seam was a fraction short of eight feet four inches but it was thought that the top three feet two inches would be left to support the tender clod roof. In order to mark the event Lord Scarbrough paid for a celebration dinner for between four or five hundred workmen and local people. It was held in a marquee put up in a field near Maltby Hall on July 9th 1910. On or about January 21st 1911, coal was reached in number one shaft. On hearing the news Lord Scarbrough immediately sent a donation to be shared between the sinkers and other workmen in recognition of their efforts. Headings were then driven underground to link the two shafts and develop the pit. The first man to lose his life after the pit had gone into production was a collier named Charles Davis who died as a result of a roof fall. Maltby was a 'gassy' pit and the danger of explosions was ever present. There has been a history of 'gob fires' which can result in explosions should the methane level in the ambient atmosphere reach approx 6%. The first significant explosion occurred in August 1911 which claimed the lives of three colliers, namely: Charles Butler, Horace Jepson and Thomas Turton. The second significant explosion occurred on the 28th July 1923 which claimed the lives of twenty seven men, twenty five of whom are still entombed in the pit workings. Modern methane extraction methods have greatly reduced the risk of explosions.

Production

The South Yorkshire Joint Line had been officially opened for freight traffic on January 1st 1909. It's records of coal movement at Maltby demonstrate increasing production year on year after 1911

1911 29,060 tons

1912 209,038 tons

1913 355,083 tons.

As the 'hand getting' of coal was reduced, and mechanisation gradually introduced, the coal output increased dramatically until, by the 1950's, it was in excess of 1,000,000 tons per annum.

Workers were continually being taken on and were arriving in Maltby from various parts of England. Namely: Staffordshire, Wigan, the North East, Notts and in the early 1950's Scotland. Maltby Model Village, complete with a Welfare Institute (stute), church, school, bowling greens, bandstand, recreation ground and allotments was built to accommodate them. Deacon Crescent was named after the MD of the Sheepbridge Iron and Coal Company, McClaren Crescent honoured one of its directors. Scarborough Crescent (nicknamed Sinkers Row) and Earl Avenue honour the 10th Earl of Scarborough. Other estates were built shortly after the model village was completed. Poets Corner, China Town, the Highfield Park/Park View area. These were followed by the Manor Estate, Cliff Hills, the White City, Birks Halt and ultimately the area which Dale Hill Road runs through. In order to quench the thirst of the population clubs and pubs were built in various locations. Libraries, recreational parks, a swimming complex and other facilities were built. In 1901 the census reported Maltby population as 716 souls. In 1911 it was 1,700 and in 1921 it stood at 7,657.

Significant Dates in the Life of Maltby Colliery

1903 Railway extension to form the South Yorkshire Joint Line applied for.

1904 Minerals lease sealed between the 10th Earl of Scarborough and the Sheepbridge Iron and Coal Company Ltd.

1905 Work on railway commenced.

1906 Maltby Main Colliery Company was registered.

1906 Site 'pegged out' in Maltby woods to accommodate shafts.

1906 First sod of earth cut in the presence of Lord and Lady Scarborough.

1907 March – Temporary sidings built to enable trains to bring materials to the site.

August – Site clearance commenced to create space for six accommodation huts.

August – Sinking of number one shaft commenced.

September – Sinking of number 2 shaft commenced.

1909 31st March – First fatalities. Arthur Horton, Sam Saunders and Charles Simmons all died as a result of an accident in the shaft.

19th August – George Henry Goodgrove lost his life when he feel into the shaft.

1910 June – Coal proved in number two shaft

July – Celebratory dinner held in local field for approx 500 local people.. Paid for by Lord Scarbrough.

1911 January – Coal proved in number one shaft. The two shafts were linked up and the pit went into production in the spring.

Lord Scarbrough then sent a donation of money to be shared between all the sinkers and other workers.

March 4th – First fatality after production commenced. Charles Davis was killed as a result of a roof fall.

August – First major explosion claimed the lives of three men: Charles Butler, Horace Jepson and Thomas Turton.

1912 Model village and crags school were completed which saw the closure of 'Tin Town' and the 'Tin School' in the pit yard. This was closely followed by other estates being built.

1914 pit now in full production.

1923 July 28th – Maltby's Black Saturday. Explosion occurred which claimed the lives of twenty seven men. Twenty five of them are still entombed in the old Barnsley workings approx 800 yards below the surface of the earth.

1947 The coal mines were nationalised and the National Coal Board (NCB) was created. This was also the year that the pit ponies were retired from Maltby Colliery and were replaced by underground conveyor belts. The ponies spent their remaining years grazing on the Miners Welfare playing fields, The end of the 1940's saw the beginning of the end for 'hand getting' coal and gradually mechanisation began to be introduced.

1950 The 50's saw the introduction of the Huwood Coal Cutter and the Meco-Moore Cutter. These machines were the forefathers of the modern coal cutting machines of today. The machines cut the coal from the face. It was then loaded onto belts which took it to the pit bottom. It was then loaded into a skip and brought up the shaft to the pit top where it was put onto another belt which took it to the washers, were it was separated from the rubbish that came up with it. Due to the methane content of the atmosphere the machines were driven by compressed air and not electricity, as was the norm in non gassy pits. Arcing from electrical components could quite easily have ignited the methane which, depending on the methane concentration, could have resulted in an explosion.

1960 The development of the deeper and less dangerous Swallow Wood seam commenced.

1972 The Barnsley seam was declared exhausted and was closed. Production continued in the Swallow Wood seam.

1981 The NCB announced an £180,000,000 development in the Parkgate and Thorncliffe seams which were deeper than the Swallow Wood seam.

1984 The year of the strike which resulted in a lot of hardship, not only in Maltby, but in mining communities throughout the coal fields. The Ascension church was opened as a soup kitchen, providing meals for up to 300 people per day. Donations of food and money arrived in the communities from a vast array of sources. In some communities there were violent clashes between picketing miners and policemen. The strike, led by NUM President Arthur Scargill, was in response to the governments planned pit closure programme.

1994 Mines were privatised and Maltby Colliery was sold to RJB mining which subsequently became UK Coal.

2007 UK Coal sold Maltby Colliery to Hargreaves.

2012 May – Higher than normal oil, water and gas ingress resulted in dangerous underground conditions and mining was suspended. It was announced that the pit would be 'mothballed'.

December – It was decided that the geological conditions would not allow mining to continue in safety, consequently the closure of the pit was announced.

2013 Maltby Colliery was formally closed

2014 The head gear was demolished and the shafts were sealed. Work commenced on demolishing the surface buildings.

END OF AN ERA.

.